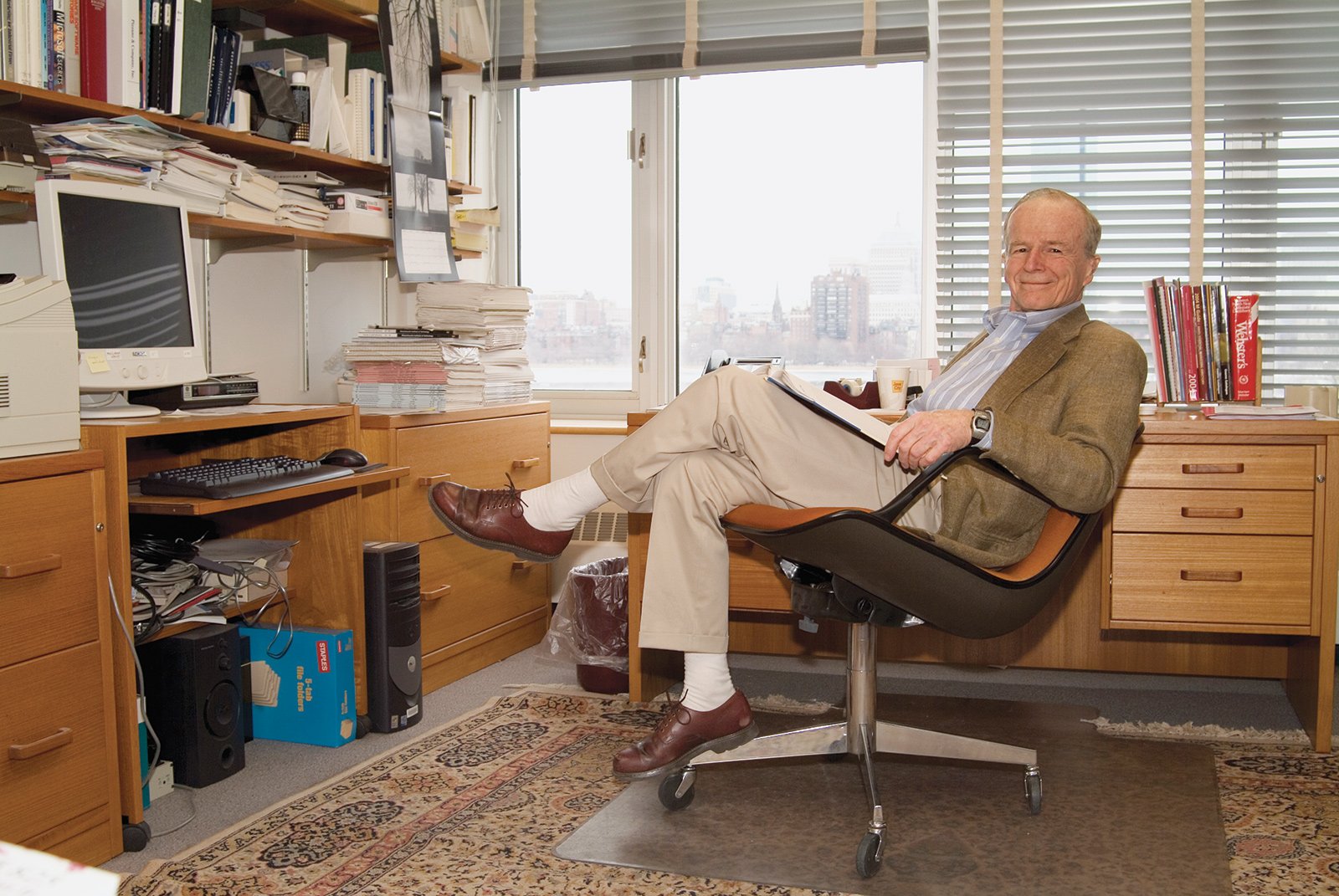

MIT Institute Professor Emeritus John D.C. Little ’48, PhD ’55, an inventive scholar whose work significantly influenced operations research and marketing, died on Sept. 27, at age 96. Having entered MIT as an undergraduate in 1945, he was part of the Institute community over a span of nearly 80 years and served as a faculty member at the MIT Sloan School of Management since 1962.

Little’s career was characterized by innovative computing work, an interdisciplinary and expansive research agenda, and research that was both theoretically robust and useful in practical terms for business managers. Little had a strong commitment to supporting and mentoring others at the Institute, and played a key role in helping shape the professional societies in his fields, such as the Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences (INFORMS).

He may be best known for his formulation of “Little’s Law,” a concept applied in operations research that generalizes the dynamics of queuing. Broadly, the theorem, expressed as L = λW, states that the number of customers or others waiting in a line equals their arrival rate multiplied by their average time spent in the system. This result can be applied to many systems, from manufacturing to health care to customer service, and helps quantify and fix business bottlenecks, among other things.

Little is widely considered to have been instrumental in the development of both operations research and marketing science, where he also made a range of advances, starting in the 1960s. Drawing on innovations in computer modeling, he analyzed a broad range of issues in marketing, from customer behavior and brand loyalty to firm-level decisions, often about advertising deployment strategy. Little’s research methods evolved to incorporate the new streams of data that information technology increasingly made available, such as the purchasing information obtained from barcodes.

“John Little was a mentor and friend to so many of us at MIT and beyond,” says Georgia Perakis, the interim John C. Head III Dean of MIT Sloan. “He was also a pioneer — as the first doctoral student in the field of operations research, as the founder of the Marketing Group at MIT Sloan, and with his research, including Little’s Law, published in 1961. Many of us at MIT Sloan are lucky to have followed in John’s footsteps, learning from his research and his leadership both at the school and in many professional organizations, including the INFORMS society where he served as its first president. I am grateful to have known and learned from John myself.”

Little’s longtime colleagues in the marketing group at MIT Sloan shared those sentiments.

“John was truly an academic giant with pioneering work in queuing, optimization, decision sciences, and marketing science,” says Stephen Graves, the Abraham J. Siegel Professor Post Tenure of Management at MIT Sloan. “He also was an exceptional academic leader, being very influential in the shaping and strengthening of the professional societies for operations research and for marketing science. And he was a remarkable person as a mentor and colleague, always caring, thoughtful, wise, and with a New England sense of humor.”

John Dutton Conant Little was born in Boston and grew up in Andover, Massachusetts. At MIT he majored in physics and edited the campus’ humor magazine. Working at General Electric after graduation, he met his future wife, Elizabeth Alden PhD ’54; they both became doctoral students in physics at MIT, starting in 1951.

Alden studied ferroelectric materials, which exhibit complex properties of polarization, and produced a thesis titled, “The Dynamic Behavior of Domain Walls in Barium Titanate,” working with Professor Arthur R. von Hippel. Little, advised by Professor Philip Morse, used MIT’s famous Whirlwind I computer for his dissertation work. His thesis, titled “Use of Storage Water in a Hydroelectric System,” modeled the optimally low-cost approach to distributing water held by dams. It was a thesis in both physics and operations research, and appears to be the first one ever granted in operations research.

Little then served in the U.S. Army and spent five years on the faculty at what is now Case Western Reserve University, before returning to the Institute in 1962 as an associate professor of operations research and management at MIT Sloan. Having worked at the leading edge of using computing to tackle operations problems, Little began applying computer modeling to marketing questions. His research included models of consumer choice and promotional spending, among other topics.

Little published several dozen scholarly papers across operations research and marketing, as well as co-editing, along with Robert C. Blattberg and Rashi Glazer, a 1974 book, “The Marketing Information Revolution,” published by Harvard Business School Press. Ever the wide-ranging scholar, he even published several studies about optimizing traffic signals and traffic flow.

Still, in addition to Little’s Law, some of his key work came from studies in marketing and management. In an influential 1970 paper in Management Science, Little outlined the specifications that a good data-driven management model should have, emphasizing that business leaders should be given tools they could thoroughly grasp.

In a 1979 paper in Operations Research, Little described the elements needed to develop a robust model of ad expenditures for businesses, such as the geographic distribution of spending, and a firm’s spending over time. And in a 1983 paper with Peter Guadagni, published in Marketing Science, Little used the advent of scanner data for consumer goods to build a powerful model of consumer behavior and brand loyalty, which has remained influential.

Separate though these topics might be, Little always sought to explain the dynamics at work in each case. As a scholar, he “had the vision to perceive marketing as source of interesting and relevant unexplored opportunities for OR [operations research] and management science,” wrote Little’s MIT colleagues John Hauser and Glen Urban in a biographical chapter about him, “Profile of John D.C. Little,” for the book “Profiles in Operations Research,” published in 2011. It it, Hauser and Urban detail the lasting contributions these papers and others made.

By 1967, Little had co-founded the firm Management Decisions Systems, which modeled marketing problems for major companies and was later purchased by Information Resources, Inc. on whose board Little served.

In 1989, Little was named Institute Professor, MIT’s highest faculty honor. He had previously served as director of the MIT Operations Research Center. At MIT Sloan he was the former head of the Management Science Area and the Behavioral and Policy Sciences Area.

For all his productivity as a scholar, Little also served as a valued mentor to many, while opening his family home outside of Boston to overseas-based faculty and students for annual Thanksgiving dinners. He also took pride in encouraging women to enter management and academia. In just one example, he was the principal faculty advisor for the late Asha Seth Kapadia SM ’65, one of the first international and female students at Sloan, who studied queuing theory and later became a longtime professor at the University of Texas School of Public Health.

Additionally, current MIT Sloan professor Juanjuan Zhang credits Little for inspiring her interest in the field; today Zhang is the John D.C. Little Professor of Marketing at MIT Sloan.

“John was a larger-than-life person,” Zhang says. “His foundational work transformed marketing from art, to art, science, and engineering, making it a process that ordinary people can follow to succeed. He democratized marketing.”

Little’s presence as an innovative, interdisciplinary scholar who also encouraged others to pursue their own work is fundamental to the way he is remembered at MIT.

“John pioneered in operations research at MIT and is widely known for Little’s Law, but he did even more work in marketing science,” said Urban, an emeritus dean of MIT Sloan and the David Austin Professor in Marketing, Emeritus. “He founded the field of operations research modeling in marketing, with analytic work on adaptive advertising, and did fundamental work on marketing response. He was true to our MIT philosophy of “mens et manus” [“mind and hand”] as he proposed that models should be usable by managers as well as being theoretically strong. Personally, John hired me as an assistant professor in 1966 and supported my work in the following 55 years at MIT. I am grateful to him, and sad to lose a friend and mentor.”

Hauser, the Kirin Professor of Marketing at MIT Sloan, added: “John made seminal contributions to many fields from operations to management science to founding marketing science. More importantly, he was a unique colleague who mentored countless faculty and students and who, by example, led with integrity and wit. I, and many others, owe our love of operations research and marketing science to John.”

In recognition of his scholarship, Little was elected to the National Academy of Engineering, and was a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Among other honors, the American Marketing Association gave Little its Charles Parlin Award for contributions to the practice of marketing research, in 1979, and its Paul D. Converse Award for lifetime achievement, in 1992. Little was the first president of INFORMS, which honored him with its George E. Kimball Medal. Little was also president of The Institute of Management Sciences (TIMS), and the Operations Research Society of America (ORSA).

An avid jogger, biker, and seafood chef, Little was dedicated to his family. He is predeceased by his wife, Elizabeth, and his two sisters, Margaret and Francis. Little is survived by his children Jack, Sarah, Thomas, and Ruel; eight grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren. Arrangements for a memorial service have been entrusted to the Dee Funeral Home in Concord, Massachusetts.

Share this content: